Last week I posted on both the Series I Savings Bond (which I have been buying for years) and the Series EE, which I haven’t bought – or even thought much about – since 1992. But that post on the EE Bond got me thinking: How is this not a good investment?

Last week I posted on both the Series I Savings Bond (which I have been buying for years) and the Series EE, which I haven’t bought – or even thought much about – since 1992. But that post on the EE Bond got me thinking: How is this not a good investment?

My advice last week was to buy the EE Bond before Nov. 1, because the Treasury might alter a key term of the bond: That your investment is guaranteed to double in value if held for 20 years. When the announcement came on Monday, the Treasury retained the double-in-20-years policy, but it dropped the permanent EE Bond’s fixed rate from 0.3% to 0.1%.

At the same time, it raised the fixed rate for inflation-adjusted I Bonds purchased from now to April 30, 2106, to 0.1% from 0.0%.

EE Bonds, really? This investment only makes sense if you are 99.999% sure you can hold it for 20 years. If you do, you will earn 3.5% on your money. If you don’t, you will earn 0.1%. So I am assuming anyone buying an EE Bond is committed to holding it 20 years. And remember, this money compounds tax-deferred. There is no tax liability until you sell.

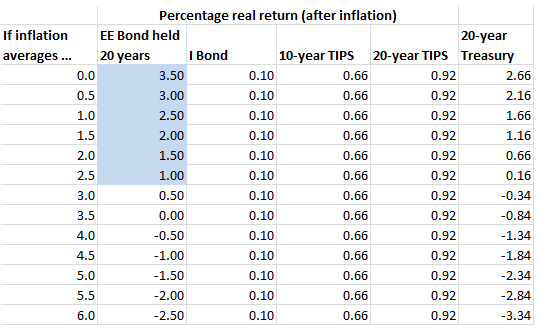

[Update: One more thought on EE Bonds; a chart explains it all …]

Back in 1992 … The last time my wife and I bought EE Bonds was in August 1992, after we sold a house and had cash to put away. At the time, EE Bonds were guaranteed to double in value in 18 years, creating a yield of 4.0%. Because of a complex dual-track rate system on EE Bonds at the time, our EE Bonds have actually yielded 5.04% over 23 years. They are still earning 4.0% a year until maturity in 2022.

It’s was my wife’s idea to buy the EE Bonds. I thought it was a horrible idea. I argued but, hey, I had to admit it was a no-risk investment. Today, $10,000 of those EE Bonds are worth $31,432, and they are still growing at 4.0% a year, all tax deferred. Good move, wife.

One more fact to complete this idea: In August 1992, a 30-year nominal Treasury was yielding 7.64%, 364 basis points higher than the official yield of the EE Bond and 260 basis points higher than the resulting effective yield.

And in 2015? EE Bonds purchased today earn a pitiful 0.1% for 19 years, 11 months, and then one month later suddenly double in value, creating an effective yield of 3.5%. How does that compare with a 20-year nominal Treasury? It is yielding 2.65%, 85 basis points below the yield on an EE Bond. Even a 30-year nominal Treasury has a yield of 3.00%, 50 basis points below the EE Bond.

So in fact, in 2015, EE Bonds are a much more attractive investment versus Treasurys than the were in 1992.

EE Bonds versus I Bonds. I remain a huge fan of I Bonds was a way of pushing inflation-protected, tax-deferred money into the future. But I think EE Bonds could make a nice addition to the super-safe allocation of your retirement portfolio.

Think of it this way: I Bonds have a fixed rate of 0.1%, meaning they will out-perform inflation by 0.1%. EE Bonds held 20 years have a yield of 3.5%. So inflation will have to average higher than 3.4% over the next 20 years for I Bonds to beat EE Bonds as an investment. Will inflation average higher than 3.4%? Who knows! It could, and that is why I like I Bonds. It might not, and that is why I like EE Bonds.

I say, buy them both.

I Bonds, of course, are a much more flexible investment. They can be sold after one year with only a 3-month interest rate penalty (same with EE Bonds), and then after five years with no penalty. No need to hold an I Bond for 20 years.

And so, I’m making a weird move. Since the I Bonds I bought in 2013 with a fixed rate of 0.0% have been composite yielding 0.0% since July 2015, I decided to sell out of that position in Treasury Direct. The 3-month interest penalty is $0. When that money comes into my savings account (within a week?) I will then purchase the new I Bonds with a fixed rate of 0.1%, up to the limit ($10,000 per person).

And … I’ll be buying EE Bonds up to the limit for the first time since 1992.

Like Justin, I usually only buy in April and October. And most years, I purchase my yearly allotment in 1…