By David Enna, Tipswatch.com

A logical strategy for some I Bond investors is to act now to redeem I Bonds with a fixed rate of 0.0% (and a current composite rate no higher than 3.94%) and use that money to invest in April 2024 I Bonds, with a fixed rate of 1.3% and a composite rate of 5.27% for a full six months.

This isn’t nuclear science, it is just simple math: A fixed rate of 1.3% is always more desirable than a fixed rate of 0.0%. That’s 130 basis points more desirable, over the potential 30 years of an I Bond investment.

Why act now?

April is the last month you can purchase an I Bond with a fixed rate of 1.3% and a six-month composite rate of 5.27%. On May 1, Treasury will be resetting the permanent fixed rate, and the variable rate will be also be reset, probably to a number lower than the current 3.94%.

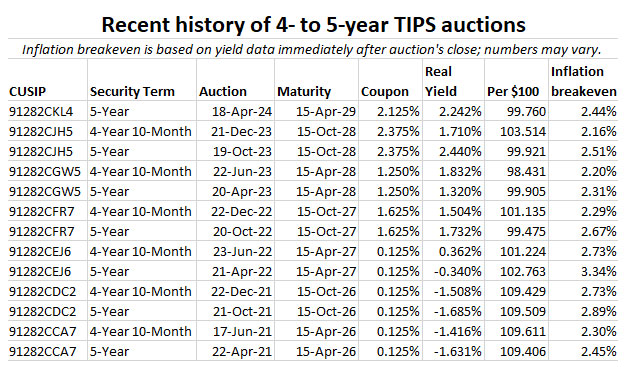

Those are big unknowns. We won’t know the new variable rate until the release of the March inflation report on April 10. I am guessing the new number will be around 2.6%. It appears likely that the new fixed rate could hold at 1.3% or slip to 1.2%, based on this updated projection:

Reminder: This projection is simply an educated guess. The Treasury has not revealed its formula for setting the I Bond’s fixed rate.

One month remains before the Treasury actually has to make a decision, and real yields have been sliding a bit lower than the daily average in recent weeks. So the trend is more toward a fixed rate of 1.20%, in my opinion. But again, this is up to the whim of the U.S. Treasury.

On the purchasing side of the equation, there is no rush. And in fact you should schedule any April I Bond purchase late in the month, because any purchase at any date earns the full month of interest. I advise setting the date no later than Thursday, April 25, or Friday, April 26, to allow TreasuryDirect time to process it in April.

But if you want to redeem 0.0% I Bonds to swap to the 1.3% version in April, you should take that action Monday or Tuesday. Why? Because when you redeem an I Bond, you earn zero interest for the month of redemption. By placing the redemption order on April 1 (which actually takes effect April 2), you will earn a full month of interest for March.

One annoying thing about TreasuryDirect is that you cannot schedule a future date for redemption (unlike purchases, where you can). So if you want to redeem on Monday or Tuesday, you should log into TreasuryDirect and do it that day.

Which I Bonds to redeem?

My personal opinion: Hold any I Bond with a fixed rate above 0.0%, at least until you have redeemed all the 0.0% issues. In fact, I generally advise holding I Bonds until you actually need the money. That is the whole idea of I Bonds. But I also admit that a 1.3% fixed rate is way more desirable than 0.0%, so swapping is a logical strategy.

Older versus newer? You can’t redeem any I Bond you have owned for less than 12 months. If you redeem an I Bond you have held less than 5 years, you will incur a penalty of the last three months of interest, applied to composite rates of 3.38% or 3.94% or a combination. If you redeem I Bonds held for more than 5 years, there is no penalty.

However …. older I Bonds will have accrued much higher interest and so the tax penalty will be higher. So, would you rather face the 3-month interest penalty, or the higher tax bill? Up to you. I am probably going to opt for the lower tax bill.

Things can get confusing. Getting ready to redeem? Log into TreasuryDirect and navigate down the page to the “Current Holdings” section. Click on “Savings Bonds”.

On the next page, navigate down to the Savings Bond section and click on the radio button for Series I Savings Bond and click “Submit”.

The next page will show a listing of all your I Bonds and show the current interest rate. The issues with 0.0% fixed rates will show an interest rate of 3.38% or 3.94%. Any other number indicates that I Bond has a fixed rate higher than 0.0%.

And now for the confusing part: TreasuryDirect shows only the composite rate, not the fixed rate.

For example, the I Bond issued April 2023 has a composite rate of 3.79%, which is lower than the two I Bonds listed below it, issued in 2022 and 2021. But that April 2023 I Bond has a fixed rate of 0.4% and through March 2024 was still on the 3.38% variable rate. As of April 1, it will be paying 4.35% and that is not a target for redemption.

In this list, I would target redeeming the 0.0% I Bonds issued in January 2022, January 2021 or April 2017. Here are the potential proceeds if I redeem the entire amounts on Monday or Tuesday:

- Jan 2022: $11,396, or $1,396 of taxable interest.

- Jan 2021: $11,696, or $1,696 of taxable interest

- April 2017: $12,684, or $2,684 of taxable interest

I am only going to do two redemptions, so I would choose Jan 2022 and Jan 2021, resulting in taxable interest of $3,092. (But also extra money I can use to travel later this year).

If you are looking at the listings in TreasuryDirect over this weekend, they will still be showing interest totals through February because March has not yet ended. I am thinking (hoping) that those totals will be updated on Monday. If they are not, I’d probably wait until Tuesday to redeem. (Can’t be too cautious with TreasuryDirect.)

Update: On Monday morning I confirmed that TreasuryDirect has updated with the March interest numbers and redemptions on Monday will be posted April 3.

And then … what’s next?

If you set up everything correctly in TreasuryDirect, the money from the redemptions should arrive in your bank or brokerage account in a couple of days.

And then, no rush if you are planning to purchase the April 2024 I Bond with the fixed rate of 1.3%. If you are positive you want to make the purchase in April you can go in immediately and schedule the purchase on TreasuryDirect’s “BuyDirect” page.

Again, I advise scheduling the purchase for late in the month, but not on the last day. Allow TreasuryDirect at least one business day to complete the transaction.

Using the gift box

If you have already purchased I Bonds up to the $10,000 limit in 2024, you could use the “gift box strategy” to purchase additional allotments to be delivered in a future year. This strategy requires that you have a trusted partner, such as a spouse, to make matching gifts.

Harry Sit of the TheFinanceBuff.com was the first to write about this strategy in a 2021 article titled “Buy I Bonds as a Gift: What Works and What Doesn’t.” When people ask me about the gift box, I point them to this article, which was well researched and thorough. So, go read that article if you don’t know about the strategy.

Some basics of the gift box strategy:

- When you place an I Bond into the gift box, it begins earning interest in the month of purchase, just like any other I Bond, and continues earning interest just like any I Bond. However, this money is no longer yours. It belongs to the recipient of the gift.

- The purchase does not count against your purchase limit for that year. It will count against the purchase limit for the recipient, in the year it is granted.

- Gift purchases are limited to $10,000 for each gift, but you can make multiple gift purchases of $10,000 for the same person. But the recipient can only receive one $10,000 gift a year, and that gift counts against their purchase limit for that year.

- You must provide the recipient’s name and Social Security Number when you buy a gift. The recipient doesn’t need to have a TreasuryDirect account … yet. Only a personal account can buy or receive gifts. A trust or a business can’t buy a gift or receive a gift.

- “I Bonds stored in your gift box are in limbo,” Harry Sit notes in his article. “You can’t cash them out because they’re not yours. The recipient can’t cash them out either because the bonds aren’t in their account yet.”

- The recipient will need to open a TreasuryDirect account to receive the I Bond. Once it is delivered, the money is the recipient’s, who can then cash out or continue to hold the I Bond.

Purchasing basics. To make a gift box purchase, click on the “BuyDirect” tab on your account homepage. Then click on the Series I radio button and click on Submit.

At this point, you will NOT be purchasing with your standard registration information. You will need to “Add New Registration” for the person receiving the gift, unless you have already done this. When filling out the information, click on “This is a gift.” at the bottom of the page.

Then, use this new registration to make a purchase. If you have done things correctly you will see “This is a gift” on the purchase review page. Then click “Submit” and you are done.

Then, logoff and log into the matching person’s account (assuming this is your spouse) and go through the same process to create a gift for yourself.

These gift purchases can be scheduled just like any I Bond purchase, and also can be canceled if circumstances change before the purchase date. Last year, I had scheduled a gift box swap with a 0.9% fixed rate, but canceled when I realized the fixed rate was likely to go higher on November 1.

In summary

I feel like I have covered a lot of ground here and may have missed some details. A lot of people have already made these 0.0% swaps, so use the comment section to provide advice if you have any. A couple of reminders:

- Wait until at least Monday to make any redemptions, so you will get full benefit of the March interest.

- Be careful to target 0.0% I Bonds in TreasuryDirect, since the site shows only the composite rate, not the fixed rate.

- Don’t feel undue pressure to make any I Bond purchases until later in April when we will know the new variable rate and have more data on the potential future fixed rate.

- And finally … there is nothing wrong with doing nothing and holding on to those 0.0% fixed-rate I Bonds. That money will continuing growing with inflation until redemption.

• I Bond buying guide for 2024: Be patient

• Confused by I Bonds? Read my Q&A on I Bonds

• Let’s ‘try’ to clarify how an I Bond’s interest is calculated

• Inflation and I Bonds: Track the variable rate changes

• I Bonds: Here’s a simple way to track current value

• I Bond Manifesto: How this investment can work as an emergency fund

* * *

Feel free to post comments or questions below. If it is your first-ever comment, it will have to wait for moderation. After that, your comments will automatically appear.Please stay on topic and avoid political tirades.

David Enna is a financial journalist, not a financial adviser. He is not selling or profiting from any investment discussed. I Bonds and TIPS are not “get rich” investments; they are best used for capital preservation and inflation protection. They can be purchased through the Treasury or other providers without fees, commissions or carrying charges. Please do your own research before investing.

Real yield is the yield above official US inflation.