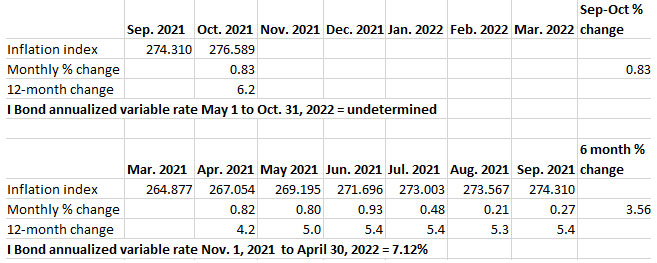

Yes, there is a slim chance we could see a higher fixed rate in 2022. But next year’s investors may still want to invest in I Bonds before May 1, to lock in the current 7.12% variable rate for six months.

By David Enna, Tipswatch.com

See my April 24 update on this topic: Let’s handicap the I Bond’s fixed-rate equation

The Federal Reserve last month began tapering its bond buying stimulus program, and hinted that it might begin raising short-term interest rates in 2022, well ahead of the expected schedule. The reason? Dangerously high inflation continues to entangle itself into the U.S. economy.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell made clear this week in testimony to Congress that inflation has been stronger than the Fed expected, and is running at a pace (an annual rate of 6.2%) that cannot be maintained. Among his comments:

“It’s difficult to predict the persistence and effects of supply constraints, but it now appears that factors pushing inflation upward will linger well into next year. …

“Generally the higher prices we’re seeing are related to the supply and demand’s imbalances that can be traced directly back to the pandemic and the reopening of the economy. But it’s also the case that price increases have spread much more broadly in the recent few months across the economy, and I think the risk of higher inflation has increased. …

“Inflation has run well above 2% for long enough that if you look back a few years, inflation averages 2%. … So I think the word transitory has different meanings to different people. To many, it carries a sense of short lived. We tend to use it to mean that it won’t leave a permanent mark in the form of higher inflation. I think it’s probably a good time to retire that word and try to explain more clearly what we mean.”

Powell’s admission that our current surge in inflation won’t be short-lived is a key concession, after months of claims the inflationary surge would be “transitory.” The result of this concession should be reflected in Fed policy: 1) quantitative easing through bond buying should be scaled back quickly, and 2) short-term interest rates should begin to rise by mid-year in 2022. Both of these actions, however, could roil the stock and bond markets, as we have seen in the last week.

Eventually, both real and nominal interest rates should begin rising, ending nearly two years of absurdly low rates, at a time when inflation has surged to a 30-year high. Finally, will investors see a reasonable return on safe investments? That’s my hope.

That brings us to the question: If the Fed truly does begin changing course (despite the likely stock market turmoil that will result) when is the Treasury likely to begin lifting the fixed rate of the U.S. Series I Bond above 0.0%, where it has remained since May 2020?

The all-important fixed rate

Even though newly issued Series I Savings Bonds currently have a fixed rate of 0.0%, they remain the most attractive very safe investment in the world. Because of the I Bond’s inflation-adjusted variable rate, investors buying I Bonds in December will earn 7.12% annualized interest for six months … and at least 3.56% over the next year (probably much higher, but that’s the worse-case scenario). Compare that to the current yield of a 1-year Treasury: 0.26%.

At this point, I Bonds don’t need a higher fixed rate to be attractive. Consider this: An investor buying the $10,000 per person per year limit in December would earn $356 in interest in the first six months. That is the equivalent of more than 17 years of interest from a fixed rate of 0.2%. For this reason, it will be almost impossible to justify not buying your 2022 allocation of I Bonds before May 1, even if you think the fixed rate will tick higher on May 1. You’ll want to lock in that 7.12% for six months.

But for investors looking to hold I Bonds as a long-term investment, a higher fixed rate is always attractive. The higher, the better.

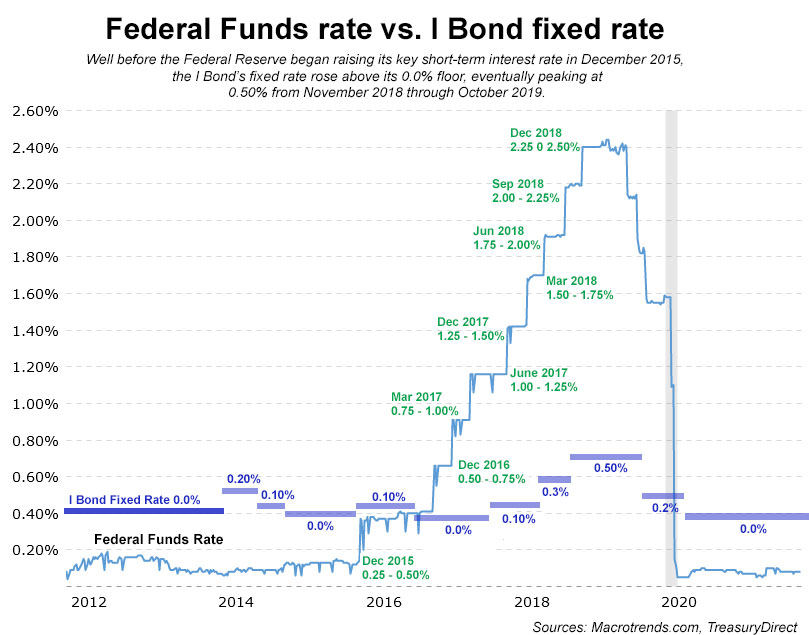

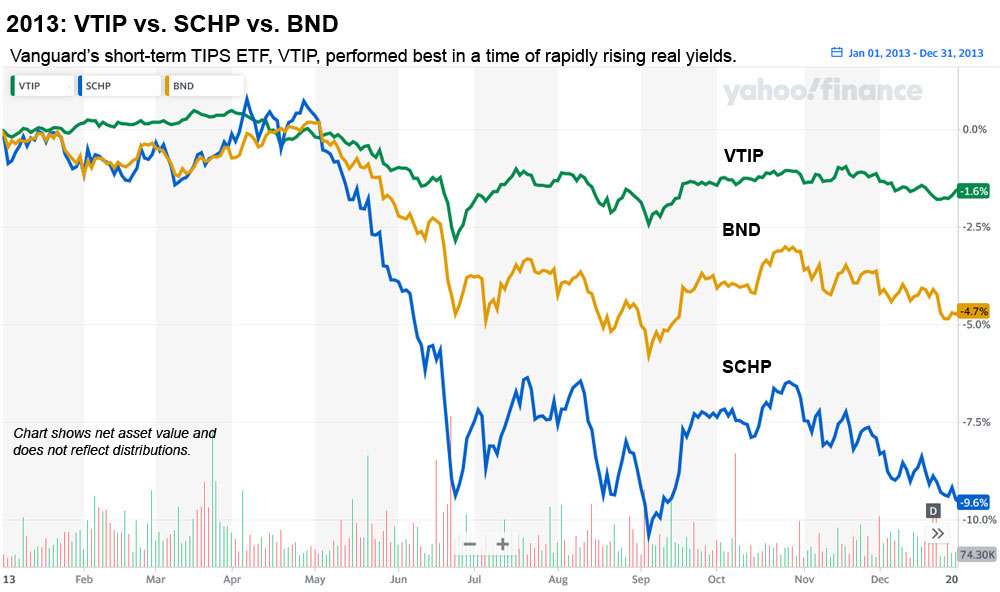

After the Federal Reserve begins pushing short-term interest rates higher (possibly in mid 2022), what are the chances we will see a higher fixed rate for the I Bond? Let’s take a look back at the Fed’s last “tightening” period, which began with hints of tapering in 2013, followed by a tapering launch in January 2014 and then finally, in December 2015, actual increases in the the Federal Funds rate.

It’s surprising to remember that the I Bond’s fixed rate rose to 0.2% in November 2013, more than two years before the Fed began raising short-term interest rates.

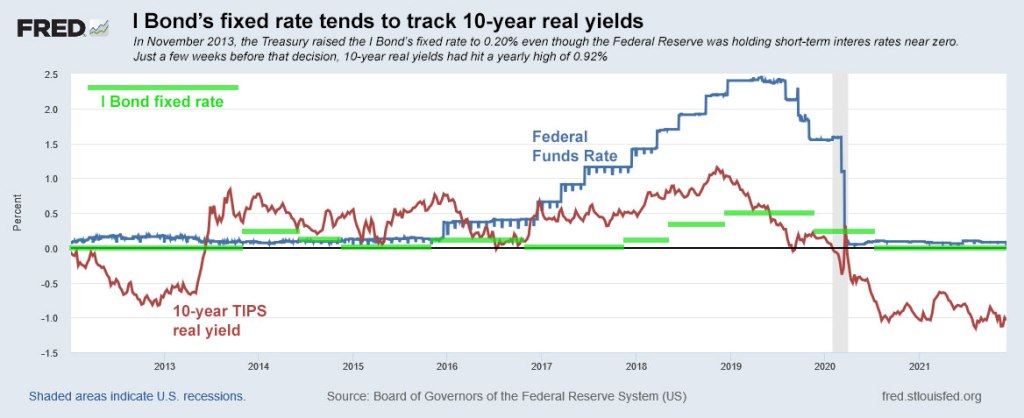

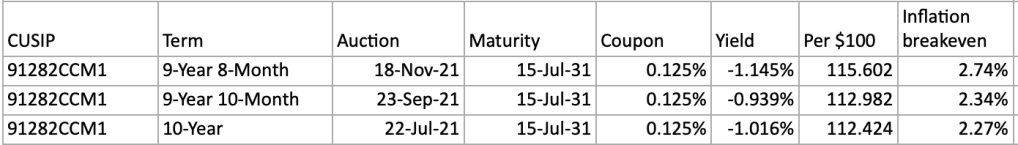

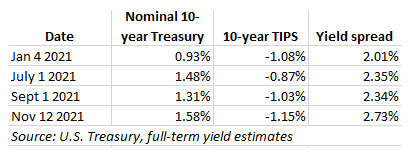

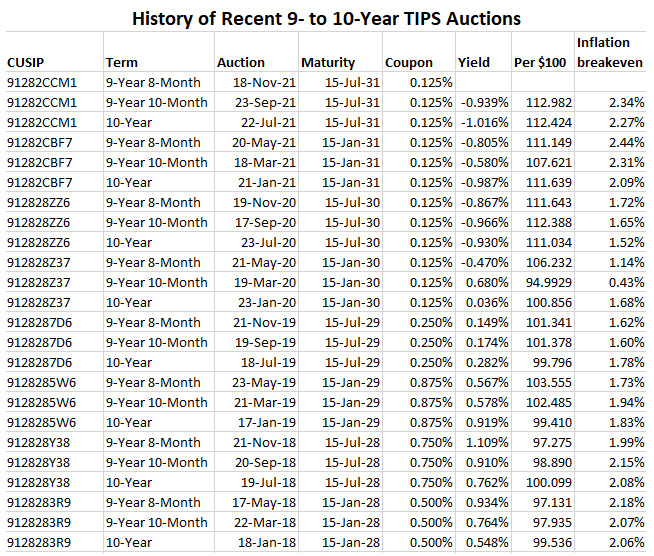

Based on this “past performance,” we can surmise that maybe the Federal Funds rate has little to do with real yields in general, or the I Bond’s fixed rate in particular. And that is true. Real yields (meaning yields above inflation, or currently, below inflation) are much more a factor of market sentiment. I contend that the I Bond’s fixed rate generally tracks 50 to 60 basis points below the real yield of a 10-year TIPS. At this point, a 10-year TIPS has a real yield of -1.08%, meaning the I Bond currently has a yield advantage of 108 basis points. Under these circumstances, there is very little chance the Treasury would raise the I Bond’s fixed rate above 0.0%.

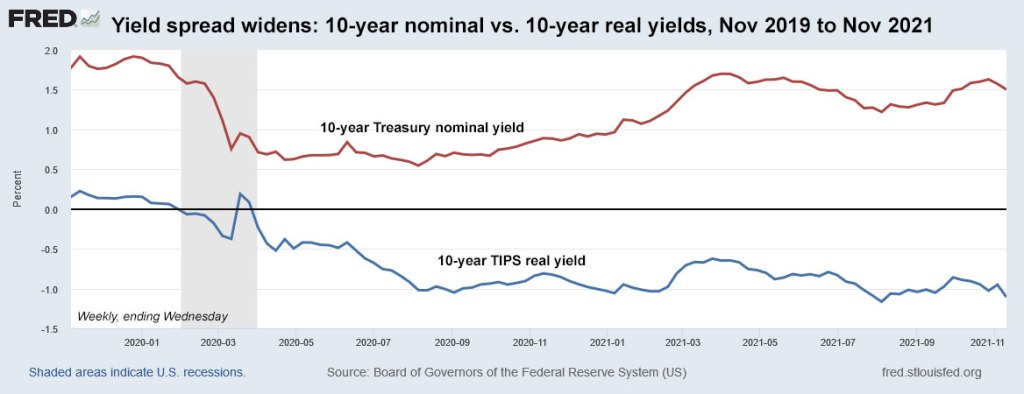

So, for the I Bond’s fixed rate to rise, 10-year real yields are going to have to climb dramatically higher, probably at least 125 basis points from today’s level. But, that isn’t really possible in 2022, is it? Actually, it is possible, as demonstrated dramatically in the Fed’s last tightening period beginning in 2013:

Note that the 10-year real yield rose a remarkable 181 basis points in the period from December 2012 to September 2013, even though the Federal Reserve 1) hadn’t even started tapering its bond purchases and 2) was still more than two years away from its first increases in short-term interest rates.

This next chart compares rate trends for the I Bond’s fixed rate, the Federal Funds rate and the 10-year real yield over the last 10 years (click on the image if you want to see a larger version):

Note that in most cases through the decade, 10-year real yields rose and fell before the Fed took action to raise or cut short-term interest rates, and the I Bond’s fixed rate rose and fell as a lagging indicator of 10-year real yields. This makes sense because the I Bond’s fixed rate is changed only twice a year: On May 1 and November 1. The Treasury makes that rate decision based on rate trends for weeks or months leading up to the reset.

When the 10-year real yield surged higher throughout 2013, the Treasury reacted with a 0.2% fixed rate in November 2013. When the 10-year real yield started slipping lower in 2016, the Treasury returned the I Bond’s fixed rate to 0.0% through November 2017. After the 10-year real yield surged to a multi-year high in late 2018, I Bonds got a fixed rate of 0.5% for a year.

A higher fixed rate is possible in 2022

To be clear, the Treasury has no announced formula for setting the I Bond’s fixed rate, and everything you just read is informed speculation. The Treasury sometimes does weird things.

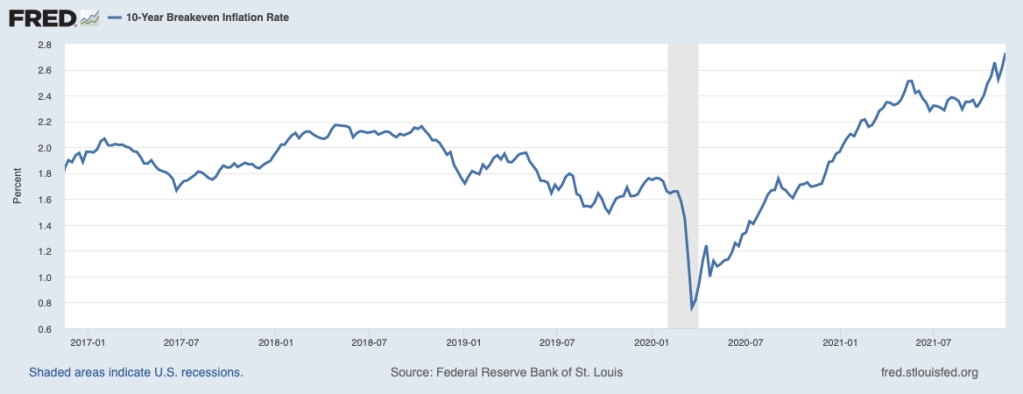

To get to a higher fixed rate, it’s going to take a mighty surge in real yields, but the example of 2013 shows that this kind of surge is possible when the Fed takes away the easy money punch bowl. The difference this time, however, is that the Fed has stated clearly that it will begin scaling back its bond buying, and real yields have barely budged. The 10-year real yield — now at -1.08% — remains close to its 2021 low of -1.19%, set on Aug. 30.

My guess is that the I Bond’s fixed rate will remain in a range of 0.0% to 0.2% through 2022. Will the fixed rate rise at or before the November 1 reset? I’d put the odds at about 15%, and that would take a giant move higher in real yields. But hey, I could be wrong.

Final thought: Can you really pass up 7.12% for six months?

Timing your I Bond investments in 2022 will take some serious thought. Will you wait it out for the chance of a higher fixed rate? I think a lot of I Bond investors will be tempted to do that. Or will you simply take the bird in the hand — a 7.12% return for six months? It will be there for the taking in January, when a new $10,000 per person purchase cap sets in.

My opinion: Waiting until mid April 2022 to make an I Bond purchase will make sense, because by then you will know the I Bond’s next variable rate, and there’s always the slim possibility that real yields will rise by 100+ basis points. But realistically, waiting until May and beyond probably won’t make sense, because as I noted earlier, the six-month return on 7.12% will be equal to more than 17 years of a 0.2% fixed rate.

Of course, the variable rate reset on May 1 could be near 7.12% or even surpass it. But remember, when you invest in an I Bond, you get the current variable rate for a full six months, and then all future variable rates will follow for six months each. Buying before May 1 looks like the logical choice.

I’ll be writing more on this topic early next year.

More on I Bonds:

- I Bond Manifesto: Why inflation-linked savings bonds can work as part of your emergency fund

- Nov. 1 update: I Bond’s fixed rate holds at 0.0%; composite rate soars to 7.12%

- I Bond podcast: U.S. Savings Bonds for a risk-free, stellar return

- I Bonds vs. TIPS: What’s the best bet for inflation protection?

- Seeking Yield And Safety? The Best Choice Is U.S. Savings Bonds

* * *

Feel free to post comments or questions below. If it is your first-ever comment, it will have to wait for moderation. After that, your comments will automatically appear.

David Enna is a financial journalist, not a financial adviser. He is not selling or profiting from any investment discussed. The investments he discusses can purchased through the Treasury or other providers without fees, commissions or carrying charges. Please do your own research before investing.

Thank you! I will need to post something soon.