The 4-week Treasury yield is sending a message of fear.

By David Enna, Tipswatch.com

Update, April 26: ‘The debt limit drama heats up,’ says Moody’s Analytics in new report

On Thursday afternoon, I happened to be watching CNBC during a long on-air interview with Cathie Wood, CEO and founder of Ark Invest, an investment management firm.

Wood is an interesting person, obviously a high-risk investor whose shoot-for -the-moon style is completely opposite mine. I find a lot of her market commentary is designed to bolster the high-risk stocks her funds already own. She’s a believer. But midway through the interview, she said something that made me jump up and say, “NO!”

Listen to the first two minutes of this clip:

Here is the quote that gave me pause:

I think the markets are leading the Fed and I was struck today to learn that the one-month Treasury bill yield is 140 basis points — 1.4% — below the low end of the Fed funds rate. I remember in ’08 and ’09 the Treasury bill rates were an early indicator of how quickly the Fed was going to ease once it realized how much trouble we were in.

What is really happening here?

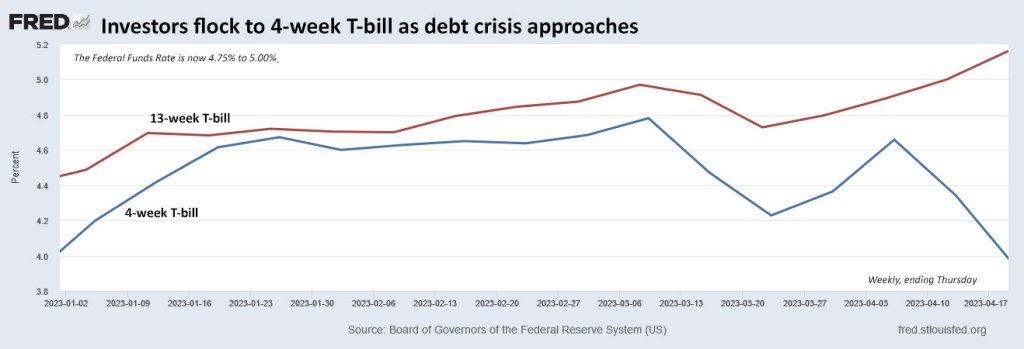

No, the bond market is not anticipating a quick turnaround by the Fed on short-term interest rates. If that were true, you’d see yields falling across all T-bill maturities. But that isn’t happening. Only the 4-week T-bill has seen yields plummet in the last three weeks, as you can see in this chart:

The chart, from the Treasury’s Yields Curve estimates page, shows that the 4-week T-bill’s yield has fallen 120 basis points in three weeks, while the 8-week is up 8 basis points and the 13-week is up 19 basis points. The same is true across the T-bill spectrum — every issue except the 4-week has seen yields rise in April.

Now, why would that happen? The reason is simple: Investors are pouring into the 4-week T-bill, forcing its yield lower, because of the near-certainty of market turmoil coming with the expiration of the U.S. debt ceiling. This is highly likely to reach “crisis” level by June, about 6 weeks from now. From the Washington Post:

If Congress doesn’t increase the limit on how much the Treasury Department can borrow, the federal government will not have enough money to pay all its obligations by as early as June. Such a breach of the debt ceiling — the legal limit on borrowing — would represent an unprecedented breakdown

If you look at the timing of this highly likely crisis, you can see that the 4-week T-bill can be purchased now and mature with a couple weeks to spare. So, in theory, it is much “safer” than the 8-week, which now has a yield 162 basis points higher. Same with the 13-week, which has a yield 178 basis points higher.

The 4-week and 13-week generally follow a similar trend line, but as the debt crisis gets closer, they have diverted:

To be clear: I am not saying that the United State will begin defaulting on its debt in June or August. That would be an utter disaster and I don’t think it will happen. But I also think there will be no resolution to this issue until we approach the brink of calamity. And that is going to cause market uncertainty.

For one thing, the yield on that 4-week T-bill will begin rising dramatically sometime in May, as we approach a potential government shutdown or debt breach.

This has happened before

2011. Back on March 6, 2023, I wrote an article (Debt-limit crisis: Lessons from the 2011 earthquake) looking back on a very similar crisis in mid-2011. This one was the most serious up to this year, but eventually was resolved on August 1. It triggered a frightening stock market collapse and solidified a near-decade of ultra-low Treasury yields. This chart shows the massive moves in Treasurys and the stock market in a single month, August 2011:

The 2011 crisis went to the brink but was resolved. Nevertheless, Standard and Poors lowered its credit rating on U.S. debt from AAA to AA+, a rating that remains in effect today.

But here is the point I wanted to make in this article: The T-bill market began anticipating the approaching crisis, with both the 4-week and 13-week T-bill spiking higher in the days before a potential government shutdown.

Of course, at this time in 2011 the Federal Funds Rate was already as low as it goes, in the range of 0% to 0.25%. So the move higher in the 4-week was only 15 basis points, from 0.01% on July 20 to 0.16% on July 29. But then again, the yield on July 29 was 16 times higher than it was on July 20.

By August 8, two days after the S&P downgrade, the 4-week yield was back down to 0.2%. In other words, the S&P action had zero effect on the U.S. Treasury market. The yield on a 10-year Treasury note was at 2.82% on July 29 and fell to 1.89% on Dec. 30. So when you hear people say, “The 2011 crisis increased U.S. borrowing costs,” just realize this is not true.

2013. A similar debt-ceiling crisis erupted in 2013 after the debt ceiling was technically reached on Dec. 31, 2012. Eventually, the debt ceiling was suspended for a few months, then reinstated. The crisis reached a peak in early October and was resolved on Oct. 16.

The chart shows the extreme, but short-lived, spike in the 4-week T-bill yield as the crisis reached a high point. Again, at the time the Federal Funds Rate was in the range of 0% to 0.25%. The 4-week T-bill yield rose from 0.1% on Sept 9, 2013, to 0.32% on Oct 15, and increase of 32 times.

What happens in a debt-lock?

I don’t think the U.S. is going to default on its debt, but there’s a real possibility we will see a short-term government shutdown and disruption to government payments. No one knows exactly how this would play out.

The Brookings Institution earlier this year issued a paper titled, “How worried should we be if the debt ceiling isn’t lifted?” It starts off with a bang:

“Once again, the debt ceiling is in the news and a cause for concern. If the debt ceiling binds, and the U.S. Treasury does not have the ability to pay its obligations, the negative economic effects would quickly mount and risk triggering a deep recession.”

In speculating on how a debt-lock could be handled, the authors note that the U.S. government created a contingency plan in 2011 at the height of the crisis:

“Under the plan, there would be no default on Treasury securities. Treasury would continue to pay interest on those Treasury securities as it comes due. And, as securities mature, Treasury would pay that principal by auctioning new securities for the same amount (and thus not increasing the overall stock of debt held by the public). Treasury would delay payments for all other obligations until it had at least enough cash to pay a full day’s obligations. In other words, it will delay payments to agencies, contractors, Social Security beneficiaries, and Medicare providers rather than attempting to pick and choose which payments to make that are due on a given day.”

You can read the full contingency plan here.

Also in March, Moody’s Analytics published a paper titled, “Going down the debt limit rabbit hole.” It predicts the actual “X-date” of potential breach is Aug. 18. It notes:

Investors in short-term Treasury securities are coalescing around a similar X-date, demanding higher yields on securities that mature just after the date given worries that a debt limit breach may occur.

Unless the debt limit is increased, suspended, or done away with by then, someone will not get paid in a timely way. The U.S. government will default on its obligations.

In discussing worst-case scenarios, Moody’s notes:

A more worrisome scenario is that the debt limit is breached, and the Treasury prioritizes who gets paid on time and who does not. The department almost certainly would pay investors in Treasury securities first to avoid defaulting on its debt obligations.

But Moody’s also notes the potential political fallout, saying, “Politically it seems a stretch to think that bond investors, who include many foreign investors, would get their money ahead of American seniors, the military, or even the federal government’s electric bill.”

I highly recommend reading through the entire Moody’s report. It presents an unpolitical and unvarnished point of view.

Final thoughts

My main point here was to show that the short-term Treasury market is already being affected by the looming crisis, and things are likely to get a lot more volatile. I don’t have answers to the “What would happen if …” questions readers often ask. We are moving into an uncertain time and the financial markets don’t like uncertainty.

* * *

Feel free to post comments or questions below. If it is your first-ever comment, it will have to wait for moderation. After that, your comments will automatically appear.Please stay on topic and avoid political tirades.

David Enna is a financial journalist, not a financial adviser. He is not selling or profiting from any investment discussed. I Bonds and TIPS are not “get rich” investments; they are best used for capital preservation and inflation protection. They can be purchased through the Treasury or other providers without fees, commissions or carrying charges. Please do your own research before investing.

REALLY appreciate the wisdom in this online community! Thank you, Dave!